Sunday, October 23, 2016

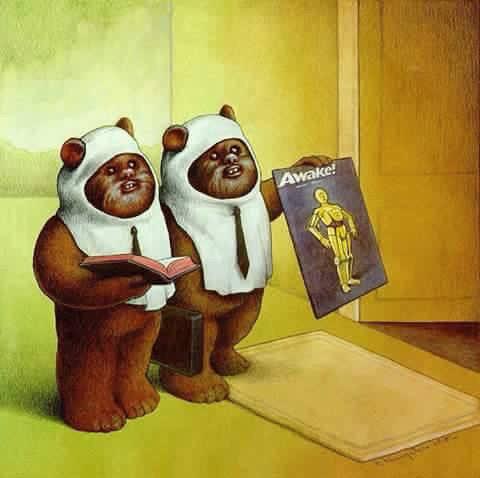

C-3PO and theology

This post is merely intended to serve as a compendium of (good quality) satirical videos, images, articles, etc., which make some connection between C-3PO and Christian (or pseudo-Christian) theology. If you know of examples that are not listed here, or if you notice any broken links here, please point them out in the comments.

Sunday, October 9, 2016

Complete list of things Donald Trump has ever apologized for

- Getting caught joking about sexually assaulting women and getting away with it because he's rich and famous.

Thursday, October 6, 2016

Don't elect Donald Trump evangelical panderer-in-chief

Someone recently sent me the article "If You're On the Fence About Your Vote, This Pastor Clarifies How the Very Future of America Is At Stake" by Dr. Jim Garlow in Charisma, in which the author makes an impassioned case for Trump as the lesser of two evils, and asked for my comments. Here they are:

- The author makes no distinction between moral and economic issues when it comes to a Christian's orientation to politics. I find that problematic. I consider myself conservative in both realms, but not because liberal fiscal policy is evil, but rather because I view it (in many cases) as irresponsible.

- The author says: "As a pastor, I would rather deal with a church attendee who is blatant and brash in his sinning than one who is devious, lying, cunning and deceptive. Both are problematic, but one is easier to deal with than the other." That may be true, but we shouldn't base our votes for president on who is easier to "correct"; we should base our votes on how they are now.

- The author further says: "Hillary's 'known' is considerably worse—many times over—than Trump's 'unknown.'" I disagree. Both have knowns and unknowns, but I prefer my favorite political writer Allahpundit's conclusions, namely, that "Trump has a bigger upside and downside than Clinton," or more elaborately: "Hillary's door might be marked 'man-eating tiger' but Trump's door is marked 'beautiful woman or nuclear war.' Which door do you want in those circumstances, where he has an upside that she doesn't but his downside isn't the same but potentially worse?"

- The author claims that Trump's "misstatements" pale in comparison to Clinton's "scandals." That glosses over the fact that Trump has some serious scandals himself (the Trump University scam, refusing to pay hundreds of contractors and employees, promising millions to various charities and paying them peanuts, etc.) and that many of his so-called "misstatements" are blatant lies, more blatant even than the lies of Hillary "Congenital Liar" Clinton.

- The author claims that "Trump is right on approximately 75 percent of the issues" whereas "Hillary is wrong on 100 percent of the issues." According to the iSideWith political quiz, my views match with Trump's 61% of the time and Clinton's 49% of the time, but with Evan McMullin's views 81% of the time. Like Garlow, "I wish it was 100 percent." But hey, I'll take what I can get.

- The author endorses nationalism over globalism and considers it a serious issue. I suppose if you share this view, it makes sense to endorse Trump. I don't share it, though I'm sympathetic to some anti-globalist impulses. I happen to believe that when, in a rare show of solidarity, virtually all economists agree that free trade is good, we should pay attention. While I believe borders should be protected and immigration regulated, I don't believe that immigration (illegal or otherwise) is the nation's scourge. I believe that we have a responsibility to our neighbors (at home and abroad) and that various NGOs are doing great work (often assisted by governments, including our own) to fight hunger, poverty, and diseases. I think Trumpism's obsession with globalism is an extreme overreaction to the real problems we face.

- The author says that "Trump has moved pro-life." "Moved" is one way to put it: he was "very pro-choice" before and during his 2000 Reform Party presidential run, even being in favor of access to partial-birth abortions, only pronounced himself "pro-life" when he first ran for president as a Republican in 2011, and has such flimsy understanding of pro-life issues that he took five different stances on the issue in three days this year. If you don't think he's merely pandering, then I have

fetal tissuea bridge to sell you. - The author says, "Hillary claims 'everything is fine' in America. This defies every single fact, but facts have never been an interest of Hillary's." Compare this to many conservatives' reactions to Michelle Obama saying in 2008, "For the first time in my adult life, I'm proud of my country," or the NFL national anthem protests. To many Americans, it would seem that the only determinant of whether America is "great" is whether or not figureheads of the opposite party currently claim that it is.

- "Trump will address the massive government spending" and "stop the massive overreach of government." Trump is a big-government authoritarian. Maybe he'll make government leaner in some areas by ruling by fiat instead of by bureaucracy, but I won't hold my breath for any balanced budgets or entitlement reform or anything else approaching fiscal conservatism.

- "Trump will expose—and I pray, bring down—'the systemic evil' (crony, deceitful, misuse of capitalism) that reigns among many high-dollar lobbyists." If you say so, Dr. Garlow, it must be so!

- "Trump fully grasps the loss of religious liberty. I have heard him speak on it in person on several occasions." I have a feeling the author was reading a lot more into Trump's statements than he was actually saying, but even if that's not the case, I doubt Trump actually backed up his teleprompter words with real conviction. His comments on his own personal faith are so nakedly about "checking the box" and nothing more (consider that he said he doesn't ask God for forgiveness because he just tries to be better, he called Communion "my little wine and my little cracker," and his favorite verse is "an eye for an eye"), that I'd be shocked if he had anything substantial or (even arguably) sincere to say about religious liberty. Moreover, on the issues that are front-and-center "culture war" issues to most evangelicals this year, Trump has been either solidly leftist or tepidly rightist (depending on the day). On transgender bathrooms, he first supported Obama's position, then decided he didn't care, then flip-flopped; on gay marriage, he's usually silent, but sometimes breaks the silence to signal his acceptance of homosexuality. Two spot-on satirical articles from the Babylon Bee sum it all up perfectly.

- The Supreme Court, another issue Garlow hypes up, is the one area that has tempted me to turn to Trumpism at times. He released a specific list of justices he might nominate earlier this year, and they were all solid. However, 1) he released another list more recently, and while there were no obvious problems with any of them (that I'm aware of), the list was very obviously not crafted for anything other than getting Ted Cruz's endorsement, and he will almost certainly not follow through on it, and 2) more generally, Trump's not exactly known for keeping his promises. 3) I was more comfortable exhorting conservative fence-sitters to vote McCain or Romney because of the justices issue, but there's a fundamental difference between those two and this one: they're actually sane. 4) Instead of using the Supreme Court as a wedge issue, we should try to reduce its effect as such by pushing for things like Supreme Court term limits (18 years), as Ted Cruz, Rick Perry, and others have.

- "I make no excuse for wrongdoing or wrongful, hurtful words from either candidate. Candidly, I want King Jesus. He rules in my heart. And yours too, I suspect. And I want Him to rule here—now. But that day is not fully manifested—yet. In the meantime, we prayerfully, carefully navigate this challenging election season, with great concern that above all, we honor our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ in every arena of our lives, including the voting booth. That is my hope. I believe it is yours as well." Amen to all that!

Tuesday, September 13, 2016

The early American welfare state

The opinions of the Founding Fathers, particularly Jefferson and Franklin, about welfare are described in an article by Professor Thomas West of Hillsdale College. West examines Jefferson's Notes on the State of Virginia (particular Query 8 and Query 14) and a few of his letters, Franklin's On the Price of Corn and Management of the Poor, and early laws. He also points out that Locke's Second Treatise states that a man "ought" "to preserve the rest of mankind" "when his own preservation comes not in competition." Franklin and Jefferson were critical of Britain's poor laws, advocated a form of social insurance, and, to put it somewhat anachronistically, advocated a liberal welfare state in contradistinction to a Social Democratic or Christian Democratic welfare state.

West states the following characteristics of the early American welfare state:

West states the following characteristics of the early American welfare state:

West goes on to state that the early system was much more effective at relieving poverty than the current system, but whether his analysis is sound or not is a question I'll leave to the economists.

- The government of the community, not just private charity, assumes responsibility for its poor. This is far from the "throw them in the snow" attitude that is so often attributed to pre-1900 America.

- Welfare is kept local so that the administrators of the program will know the actual situations of the persons who ask for help. This will prevent abuses and freeloading. The normal human ties of friendship and neighborliness will partly animate the relationship of givers and recipients.

- A distinction between the deserving and undeserving poor is carefully observed. Able-bodied vagabonds get help, but they are required to work in institutions where they will be disciplined. Children and the disabled, on the other hand, are provided for, not lavishly but without public shame. The homeless and beggars will not be abandoned, but neither will they populate the streets. They will be treated with toughness or mercy according to their circumstances.

- Jefferson's idea of self-reliance was in fact family reliance, based on the traditional division of labor between husband and wife. Husbands were legally required to be their families' providers; wives were not. Nonsupporting husbands were shamed and punished by being sent to the poorhouse.

- Poor laws to support individual cases of urgent need were not intended to go beyond a minimal safety net. Benefit levels were low. The main remedy for poverty in a land of opportunity was marriage and work.

Monday, July 25, 2016

My most politically incorrect opinion

No, it's not that people should eat the poor (or the rich). My most politically incorrect opinion is that society should reintroduce corporal punishment as an option for dealing with criminals. Hey, I warned you it was politically incorrect.

Why would I be so barbaric? Instead of me telling you, I'll enlist the help of the late theologian John Wenham's woefully obscure book The Goodness of God. Disclaimer: he doesn't directly defend the idea of corporal punishment here, but it's still the passage that convinced me it's a good thing. If you enjoy or are edified or challenged by this passage, I encourage you to buy or rent the book and experience its goodness for yourself.

Why would I be so barbaric? Instead of me telling you, I'll enlist the help of the late theologian John Wenham's woefully obscure book The Goodness of God. Disclaimer: he doesn't directly defend the idea of corporal punishment here, but it's still the passage that convinced me it's a good thing. If you enjoy or are edified or challenged by this passage, I encourage you to buy or rent the book and experience its goodness for yourself.

Whether in fact the Old Testament laws were cruel in comparison with those of our supposedly humane society is not as self-evident as many think. The Old Testament relied mainly on payment of damages, strictly limited corporal punishment and capital punishment, whereas modern society relies mainly on fines and imprisonment. The nearest thing to imprisonment in Old Testament law was confinement to a city of refuge for unintentional homicide. The question of punishment is such an emotive subject that one almost despairs of its rational discussion. Anyone who defends corporal or capital punishment even in the most tentative way runs the risk of being branded as a sadistic ogre. Yet my horror of long-term imprisonment is horror at the sheer suffering that it entails. Far from being insensitive, I hate undergoing pain and seeing pain inflicted. Even though reason leads one to believe that the suffering is not nearly as bad as it looks, I hate to see a fly wriggling on a fly-paper or a fish struggling on a hook, and get little pleasure from watching amateur boxers knocking one another about, despite the knowledge that they do it because they enjoy it!

One would hate, therefore, really to hurt someone physically by way of punishment, and would deplore any system of corporal punishment which was either sadistic in intent or excessive in degree, or which was used without due consideration of the offender’s psychological needs. Even more would one shrink from joining the firing-squad and taking part in an execution. But would this mean having relatively little qualm about committing a man to prison for a decade? If one had no imagination and no compassion, it would of course by easy – no unpleasantness, no soiling of the hands, soon out of sight and out of mind. But in fact my slight experience of prisons and criminal asylums fills me with dismay. To substitute long imprisonment for execution may at first sight seem like mercy. But judged by the suffering to be endured it is, surely, the reverse of mercy.

Long imprisonment is a living death. A man is separated from his wife and family (often causing them prolonged, unmerited hardship), he is put in a single-sex institution where a normal sex-life is impossible, his companions are criminals, he is shut up to his own bad conscience, but in conditions ill-designed to effect repentance and reformation and with slender hopes of satisfactory rehabilitation after release. With unlimited money and with angels for warders (which, realists please note, will never be), some of these evils might be considerably mitigated, but nothing can do away with the fact that a human being is deprived of his liberty. This aspect of the matter is highlighted in our top security gaols, which may be clinically hygienic and immaculate in décor, but in which men of drive and brains and initiative rot out their days. It is true, of course, that the human spirit has a remarkable resilience even in appalling circumstances, and that life, however bad, is seldom one of unrelieved misery; some sort of mode of living is worked out in prison life, in which its lights and shades continue to be felt with pleasure and displeasure. It is often true too that the life out of prison of one who has fallen foul of society may already have lost many of the elements which make up a fully human life, so that in some respects life in prison may be less unpleasant than life outside. (Such men are often at least as much victims of a cruel society as its creators.) But it is a poor defence of long-term imprisonment to say that it is merely substituting one dehumanizing process for another.

If (per impossibile) some sort of calculus could be devised to assess the amount of suffering cased to offenders and their families by our long-drawn-out, physically painless punishments, and compare them with the short, sharp pains of the older punishments, I find it hard to believe that the new would prove the lighter. Furthermore, even in the most enlightened and affluent society, it is an enormous struggle to get adequate funds and suitable staff to run our penal institutions (and in a fallen society it seems unrealistic to believe that it will ever be otherwise). But in the poor, largely rural society of the Old Testament, the provision of humane, secure, long-term prisons would have laid an intolerable burden on the community – apart altogether from the suffering and corrosion of character caused by the loss of liberty.

It is all very well to talk in theory about the enlightenment and humanity of modern penal codes, but in practice the prisons of the twentieth century have probably witnessed torments as vile as those inflicted in any age and inflicted on a wider scale than ever before in history. We think naturally of Hitler’s concentration camps, of Japanese prisoner of war amps and of the prisons described by Solzhenitsyn. One’s mind is numbed as one tries to compute what it all adds up to in human terms. These examples (which come from three of the most ‘civilized’ nations of the world) are, it is true, very bad cases, but they are, alas, not isolated examples. Like the mushroom cloud of the atom bomb they are symbolic of our age. The inescapable fact appears to be that sin will take its toll of misery somehow. The primitive barbarity and the cheapness of life in the ancient Near East is dreadful to contemplate, but is our sophisticated barbarity really less dreadful? No society can hold together without punishment of transgressors, and punishment is by definition unpleasant. Are we really in a position to say that we could have devised for the Israelite people unpleasantness more just, humane and practical than those prescribed in the Old Testament law? I for one doubt it.

…

It is a principle [in the Old Testament law] that punishment allows the offender to make atonement and be reconciled with society. After he has paid the penalty the offender suffers no loss of his civil rights. Degradation of the offender as a motive for punishment is specifically excluded by Deuteronomy 25:3, where the number of strokes is limited to forty, ‘lest, if one should go on to heat him with more stripes than these, your brother be degraded in your sight’. The degrading brutality of many punishments under Assyrian law is in marked contrast to the Hebrew outlook.If you're still with me, check out C. S. Lewis' essay "The Humanitarian Theory of Punishment" (included in the essay collection God in the Dock) for a defense of capital punishment and retributive justice.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)